Playing the CyberSultan: Videogames and the Islamic Empire

Video games like the "Crusader Kings" and "Civilization" franchises are laboratories for experiencing complex and nuanced historical imaginaries. But even the most well-researched tend to perpetuate certain stereotypes about Islam and the Middle East...

We all know that representations of Islam and the Middle East in the movies tend to be woefully prejudiced. Think of the opening song in Disney’s Aladdin (1992): “It’s barbaric, but hey! It’s home!” Videogames are no exception: even the most nuanced, such as the Crusader Kings franchise (the third edition of which is coming out in a few days) reproduce nineteenth-century stereotypes. A review of the 2012 Sword of Islam expansion of Crusader Kings II was given the breathless title “Play a Game as a Medieval Islamic Ruler. For Once.” The reviewer lauds the game for going beyond just using Muslims as the bad guys for Europeans to beat up.

And I have to say, the level of detail in this game is truly impressive, as its detailed wiki makes clear. Muslims are not presented as homogenous, but include Sunnis, Shia, and Kharijis – each of which has further subdivisions. It has, however, some weird mistakes: “Sunni Islam has two playable heresies, Yazidism and Zikrism.” Yazidism is very definitely not a sub-sect of Sunnism, or indeed a sect of Islam at all. It is a shame that such small and interesting groups with distinctive creeds are flattened and denigrated as “heresies”: divergences from a larger “orthodoxy.” This is, indeed, a rather medieval way of looking at the world.

On the plus side, we get to see some obscure historical actors entering the limelight, including the Marinids and Wattasids in North Africa. This detailed research notwithstanding, interviews here and here with the leader of the Sword of Islam project, Henrik Fåhraeus, show him parroting some hair-raising orientalist tropes, including that old bogey, Oriental despotism. As Fåhraeus puts it, “You’re this despot, you don’t have to worry about pleasing your vassals in the same way [as Christian kings].” The idea that all of Christian Europe has always been intrinsically more democratic than the Middle East is just wrong. In any empire, the assent of its subjects and stakeholders is crucial to success, as we are finding out in our EmCo project, which has shown us how the Islamic empire was founded to a crucial degree upon the assent, and participation, of non-Muslims and non-Arabs.

The designers also introduced a Khaldūnian mechanic called “decadence.” As Fåhraeus explains it: “There are many examples from history where a tribe or clan from the fringes of the realm suddenly rose up to seize power from what they viewed as a weak ruling dynasty of decadent city dwellers.” Well, maybe so, but conquest from the peripheries is not a Middle Eastern exception. And calling it “decadence” suggests that Middle-Eastern people are just more likely to stagnate than their European counterparts… As if the crony-dictatorships of twentieth and twenty-first century Arab countries were always inevitable, even though medieval Baghdad was more vibrant, cultured, clean, and technologically advanced than medieval Paris or Aachen.

Am I being pedantic? As Fåhraeus notes, “In general, gameplay always comes before historicity for us…We took inspiration from historical processes and differences.” OK, that is reasonable, but does it need such a regressive conceptual framework? The problem is that this kind of language entrenches the vision of the East as following intrinsically different historical rules from Europe, a vision familiar to academics in Max Weber’s conception of progress as driven by Protestant values; or Bernard Lewis’s leading question as to “what went wrong?” in the Middle East.

The game also reproduces a narrative that, although all of the actors rely on religious sources of legitimacy, Muslims have somehow historically been more religious (read “fanatical” in the old parlance). As Fåhraeus puts in, “Muslims will also tend to have more Piety to spend.” This idea really does not stand in a medieval world of crusades and excommunications.

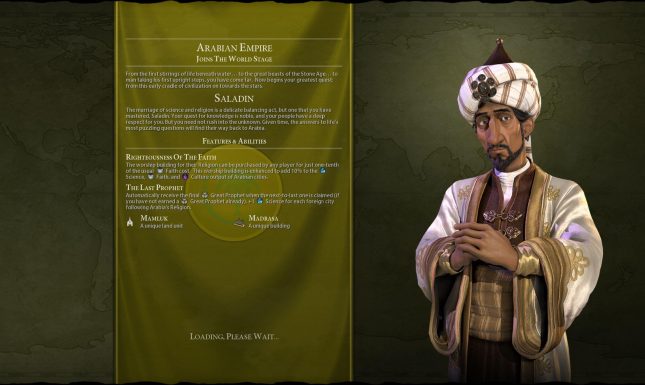

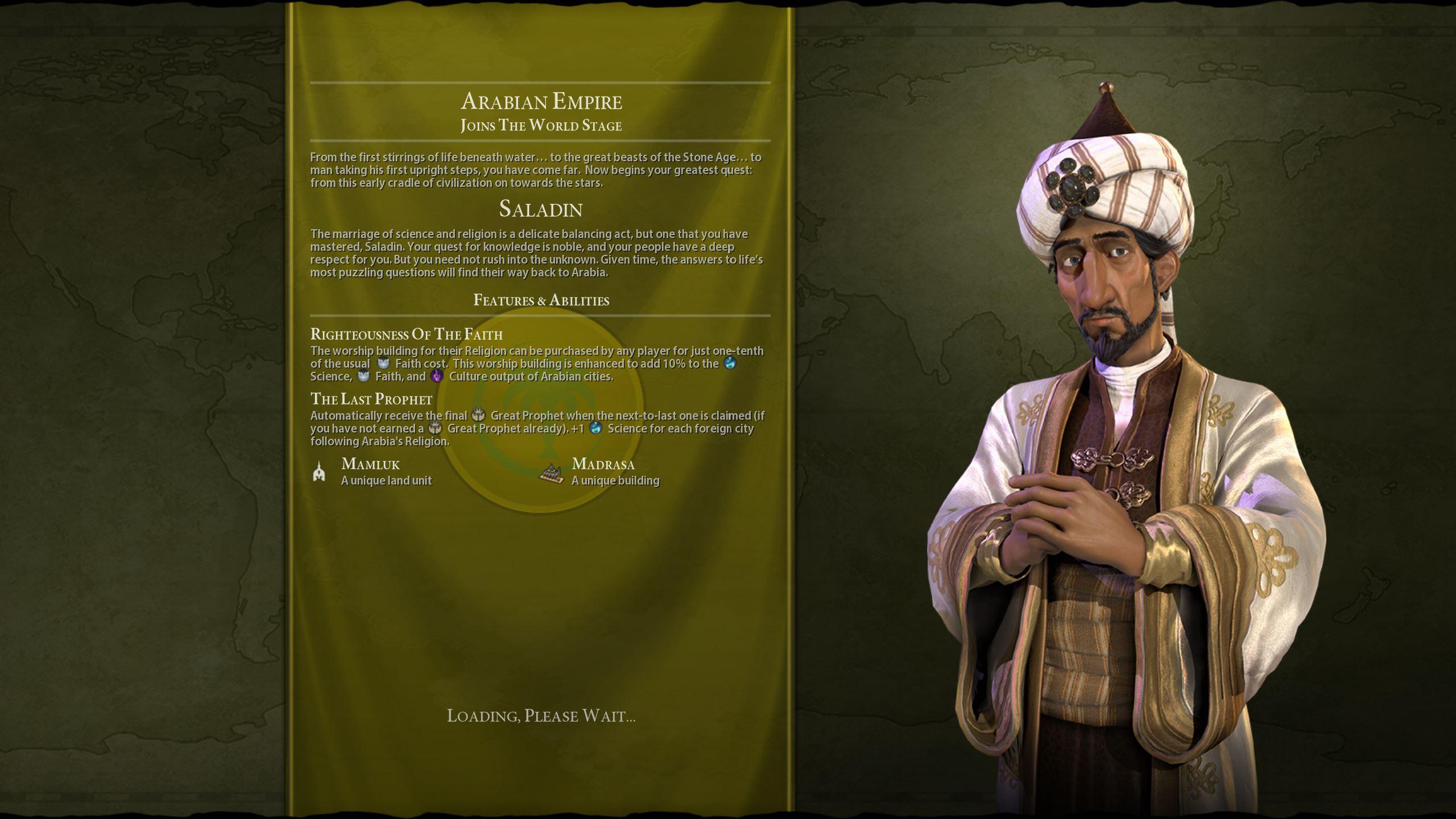

The idea that Muslims are intrinsically more religious returns more subtly in another giant of the strategy game world: the sixth edition of Civilization. Academic Vit Šisler praises the Civilization games: “The ingame description of many features of Islamic civilization is unique for its correctness and sensitivity.” Even so, if you opt to play Saladin (who, although he was probably a Kurd based in Syria, for some reason rules the “Arabian Empire”) your special abilities are linked to religion. As the Fandom wiki tells us, Saladin “dislikes leaders who follow other Religions or wage war on followers of his Religion. His leader bonus is Righteousness of the Faith, which … provide[s] bonus Science, Faith, and Culture.” Well, Saladin certainly was a committed Muslim ruler… but surely not more pious than many medieval European rulers. Remember the Crusades? Divine Right of Kings? Heck, look at Donald Trump misquoting bits of the Bible to get the Christian vote. Even Civilization VI’s laudable range of cultural options subtly perpetuates the mistake that the Middle East and Muslims have always been more influenced by religion than other regions.

Games allow you to inhabit another person’s subjectivity. This can be a powerful route to more nuanced ways of thinking about culture, about the past, about how history might have altered if “played” a different way. But this experimentation with history cannot happen if games start by weighting the scales. If Muslims are engineered to be intrinsically more religious from pious non-Muslims, then we cannot move beyond our preconceptions to normalize the Middle East as part of the history of the world instead of an exotic exception.

For further blogs by Edmund Hayes visit the Embedding Conquest website.

0 Comments