Muslim Pilgrimage in Bali

In Indonesia, ziarah or pilgrimage to sacred sites is a booming industry: every day, thousands of Muslims make a pilgrimage to the graves of Muslim saints on Java, but increasingly also to graves on Bali, a Hindu island. Syaifudin Zuhri saw ziarah on Bali become a phenomenon among Javanese Muslims.

Ziarah to the graves of the Nine Saints of Java (Walisanga) is a widely performed pilgrimage among Indonesian Muslims, but it is not the only one. Muslims also make pilgrimage to the graves of the seven Muslim saints (Wali Pitu) on Bali. This may seem surprising, since Bali is a prominent Hindu island and a ‘Hindu museum’ in contemporary Islamised Indonesia. Muslims form a small minority group on the island and are known for their foreign origins. They trace their origins mainly to the settlers from Java, the Buginese from South Sulawesi (Makassar), the Sasak from Lombok, and to Balinese Muslim converts, particularly the commoners who do not belong to the three Balinese castes (triwangsa).

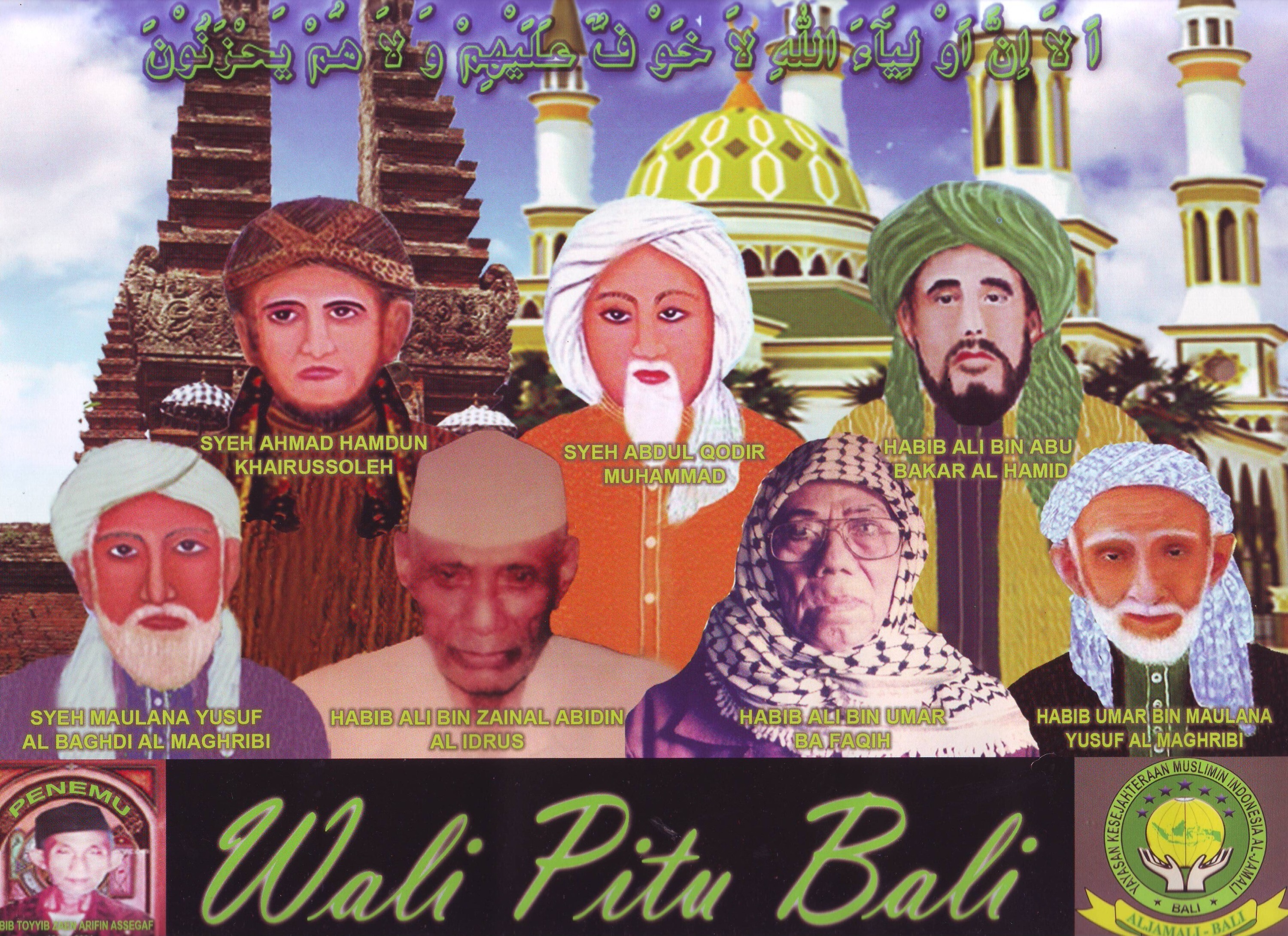

Wali Pitu refers to seven individuals deemed Muslim saints whose graves are located on Bali. They are Habib Umar bin Maulana Yusuf Al-Maghribi, Habib Ali bin Abu Bakar al-Khamid, Habib Ali bin Zainal Abidin al-Idrus, Habib Ali bin Umar Bafaqih, Shaykh Yusuf al-Baghdi, The Kwan Lie or Shaykh Abdul Qadir Muhammad, and Mas Sepuh or Raden Amangkuningrat. Four of the Wali Pitu members bear the honorific title habib, the equivalent of sayyid (male descendants of the Prophet Muhammad), whereas two have the title shaykh, particularly referring to non-sayyid Arab descents, and one has the title raden, designating a noble aristocratic origin from Java. The mix of foreign (Arab and Chinese) and Javanese saints is similar to that of the Javanese Walisanga.

The Wali Pitu concept comes from a Javanese religious leader or kyai, Toyyib Zaen Arifin (1925–2001). He claimed to have heard a divine voice (hatif) in Javanese instructing him to go and find the graves of seven Muslim saints on Bali in 1992. Following the instruction, Arifin established his pseudo-Sufi congregation named Al-Jamali, exclusively intended for Javanese Muslims living on Bali. Since the foundation of Al-Jamali, Arifin has regularly visited Bali to lead the rite of reciting the Nur al-Burhan, the hagiographical text of the Persian Sufi, Abdul Qadir al-Jilani (1077–1166).

After six years, Arifin eventually identified all seven graves of the Wali Pitu and documented his discovery through the publication of Manakib Wali Pitu, the hagiography of the seven saints, in 1998. This hagiography is the earliest textual source on the Wali Pitu. Importantly, Arifin and the members of Al-Jamali also created the visualisation of the Wali Pitu, with Arifin’s photo and Al-Jamali’s logo on the bottom left and right of the Wali Pitu image. They actively organised the haul (annual commemoration) of the Wali Pitu and promoted it by giving sermons and distributing brochures. Arifin also invited Javanese Muslims to visit Bali and perform the pilgrimage. Ziarah to the graves of Wali Pitu grew to be big business in Bali, involving a vast number of ziarah entrepreneurs – including religious leaders specialising in pilgrimage (kyai ziarah), tourist guides, travel agencies, and organisers of religious tourism (wisata religi). When visiting the graves of Wali Pitu in 2016, I met hundreds of pilgrims every day, particularly Javanese Muslims, performing pilgrimage to the graves of Wali Pitu through wisata religi.

Despite the rising popularity of wisata religi to the graves of the Wali Pitu among Javanese Muslims, Wali Pitu as a discourse is contested and, to some extent, problematic. For Muslims residing on Bali, especially non-Javanese Muslims – such as Buginese and Balinese – the Wali Pitu represents a Javanese invasion of their religion and culture. They consider it as a Javanese invention for the sake of tourism and even, at worst, as a threat to the Islamic faith or sinful idolatry (shirk). However, in the case of the grave-turned-temple of Mas Sepuh in the Hindu village Seseh, which is one of the most visited graves of the Wali Pitu, the controversy is less, as the grave welcomes both Muslim and Hindu pilgrims: they see the grave as a burial site of their prince.

Further reading: Wali Pitu and Muslim Pilgrimage in Bali, Indonesia: Inventing a Sacred Tradition, by Syaifudin Zuhri. Leiden University Press, 2022.

0 Comments