Living among the Dead? Cemeteries and Burial Practices in Post-War Sarajevo

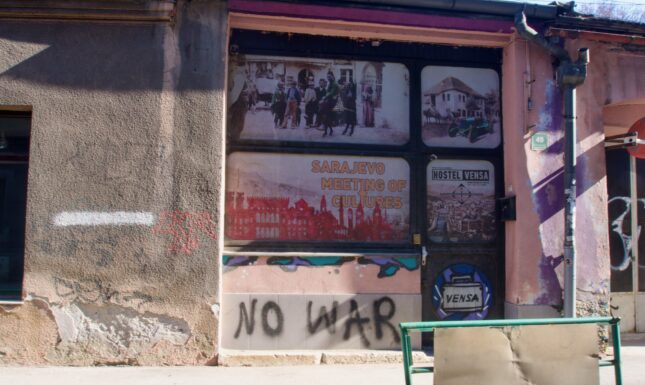

In Bosnia’s capital Sarajevo the dead are omnipresent. Why do people bury their dead near the living, and what role do war and religion play? Nadia Sonneveld and Kerim Sušić strolled through various cemeteries and neighbourhoods in Sarajevo in search of answers.

You cannot escape it: the mountains surrounding Bosnia’s capital Sarajevo are dotted with numerous white cemeteries. But it is a common sight to see children play among tombstones in the centre of Sarajevo too. One gets the impression that life and death in this post-war city are intimately intertwined.

From 1992 until 1995, the newly independent country of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) went through a devastating war in which ethnicity and religion were used to justify mass killings. The three main ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina are, in alphabetical order, Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), Bosnian-Croats (Bosnian Catholics), and Bosnian-Serbs (Bosnian Orthodox Christians).

From the surrounding mountains, the multi-ethnic and multi-religious city of Sarajevo was besieged by Bosnian-Serb forces from April

1992 to February 1996. An estimated 9,502 people were killed during the siege, including 4,954 civilians and 4,548 soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBIH). This number is not definitive as some people are still missing.

The Dayton Peace Agreement of 1995 ended three long years of war. It was agreed that Bosnia and Herzegovina would be divided into two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where most Bosniaks and Bosnian-Croats live, and Republika Srpska, where most Bosnian-Serbs live. It was decided that Sarajevo, including some areas that were under Bosnian-Serb control during the war, would be in the Federation of BiH. The arrangements led to around 60,000 Sarajevan Serbs leaving the city a few months later, between January and March 1996. Presently, Bosniaks form 77.5% of the population in Sarajevo, while Bosnian-Serbs and Bosnian-Croats form 12% and 7.5% of the population, respectively. The remaining 3% is classified as ‘others’ and consists mostly of Sephardic Jews and Roma.

Religion

“When I open my window in the morning, I look out on a cemetery. I have no problem with that. It shows me every single day that we will die and that we must live our lives well. In other countries, cemeteries are surrounded by walls, to hide what is all awaiting us. But if you are aware of your own finiteness, you understand your role in the world better.” Referring to a cemetery next to a mosque, Nihad Kreševljaković, the director of the International Theatre Festival Sarajevo, voiced sentiments that were clearly widespread.

According to many Bosniaks, cemeteries remind you that earthly existence is short and merely a passage to another, eternal, life. To gain the gift of eternal life, you have to live well now. One respondent said that a cemetery around a mosque is called harem, to denote it is a sacred and respected place, and to remind people that life and death are connected.

Sarajevo is dotted with cemeteries attached to small mosques. They were built during Ottoman rule (mid-15th century–1878). The mosques and cemeteries fall under the responsibility of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina, an independent religious organisation established in 1882.

In contrast, Christian (i.e. Catholic and Orthodox) graves in Sarajevo exist more separately from churches and residential areas. This might lead us to conclude that living near the dead is a Muslim phenomenon in Sarajevo. Yet, there are also other reasons why Muslims bury their dead near the living.

War

Before the war, many Sarajevans buried their dead at Bare cemetery, a public cemetery five kilometers outside the city of Sarajevo with assigned plots for Atheists, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and Orthodox Christians.

During the war, Bare cemetery was unreachable due to the proximity of the front lines. The shelling and snipers made it simply too dangerous to go to Bare. This made little difference to Catholics and Orthodox Christians, who had alternative cemeteries in the city centre that were safely reachable.

Muslims, however, had no such facilities in the city centre. They started using the football pitch in the Olympic Stadium to bury their dead, for security reasons and because it was one of the few large open spaces available in the city. This new cemetery was adjacent to the already existing Catholic and Orthodox cemeteries located next to the stadium.

Another possibility during the war was Groblje Lav (Lion Cemetery), a public cemetery dating from 1917, which originated from a plan to create a military cemetery where fallen Austro-Hungarian fighters, including a Bosnian regiment within the army, would be buried. Located opposite the Olympic Stadium, it has plots for Atheists, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Orthodox Christians as well as the Austro-Hungarian soldiers who died in the battle of Monte Melleti in 1916. At this graveyard, it is not uncommon to see Muslim and Christian graves next to each other; during the siege, the unofficial rule that people of different religions (including people from mixed marriages) should be buried on separate plots, was relaxed.

People living in the suburbs of Sarajevo, by contrast, often had to bury their dead in front of apartment buildings, at night. After the war, most bodies were exhumed and reburied in cemeteries, but not all. This explains why it is not unusual to see tombstones alongside houses today.

In other cases, Muslims were buried in the graveyards next to the many small mosques in Sarajevo.

Fallen ARBIH soldiers are buried mainly at Kovači cemetery at the edge of the city centre, but also at smaller cemeteries throughout the city and in the hills where white pillar-shaped headstones usually display in Arabic al-Fātiha, the name of the first sura of the Qur’an, with written below it, in Bosnian, verse 154 of sura al-Baqara, a clear reference to the fallen being revered as martyrs.

Although in significantly smaller numbers, Bosnian-Serbs and Croats also fought in the ARBIH. Except for a few cases who are buried in the cemeteries for martyrs, there are memorials to fallen Christian, Atheists, and Muslim fighters, with their names written on them, throughout the city.

Currently, most graveyards in the city centre, both public and private, Muslim and Christian, are full. The Bare cemetery is also full. In 1985, a new public cemetery 20 kilometres outside Sarajevo was inaugurated. Gradsko Groblje Vlakovo (Vlakovo City Cemetery) has the same design as Bare cemetery with different plots for the four religions mentioned earlier and Atheists. But securing a place is not cheap and, allegedly, this leads some Sarajevans to resort to burying their dead on the other side of the mountain, at Groblje Miljevići, a multi-confessional cemetery located a few hundred metres into East Sarajevo, where Republika Srpska begins, and where prices for plots are lower.

Sarajevans hardly have the space and financial means to bury their dead near the living any longer. The dead have moved out of the city centre and the hills of Sarajevo, and have occasionally even crossed ethnic and territorial dividing lines that are still very present in daily life, but perhaps not so in death.

0 Comments