Chopping Off Hands and Other Colonial Stereotypes

Sanne Ravensbergen looks at 'penghulus,' Islamic advisors to Dutch judges in colonial Java. The Dutch fostered an image of the penghulu as an old, passive official whose only advice was to chop off a hand, but actual case files paint a subtler picture.

In 1918 a Dutch colonial judge wrote in a newspaper article that when he consulted the Javanese Islamic advisor—the penghulu—during a criminal court case, the penghulu always used “one or another Arabic phrase for an Islamic punishment,” and his advice sounded “as a hollow, unknown sound which therefore immediately gets lost”.

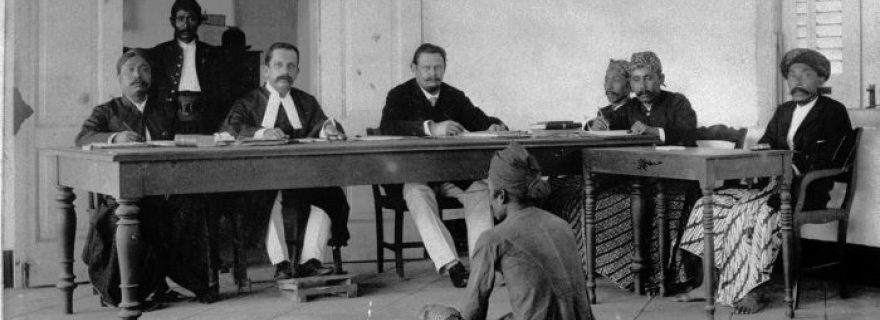

This description of the penghulu in colonial discourse is exemplary for how Dutch colonizers depicted and approached Islamic law in colonial Indonesia. Most colonial lawyers expressed little interest in the workings and writings of the region’s Islamic legal traditions. And although it was mandatory to consult the penghulu’s advice in court cases where the suspect was Muslim, this advice was hardly followed. Colonial judges claimed that the penghulus’ “archaic advice” to cut off the right hand in theft cases was the reason for ignoring their advice altogether.

Penghulu literally means head, leader, or chief, and in (pre-) colonial Java it was the title of the highest-ranking religious official. Colonial officials, however, increasingly presented a stereotypical image of the penghulu as an old, passive official who hardly spoke Arabic, fell asleep during court sessions, and always recommended potong tangan, or cutting off a hand.

This image resonates in most historical works on colonial Java where the penghulu is often only mentioned in the context of corporal punishments, briefly described as a marginal figure, or not mentioned at all.

However, early nineteenth-century law cases kept in the Indonesian national archives (ANRI) in Jakarta tell a different story. A story that sheds more light on the early days of the penghulus’ arrival in the colonial courtroom and on their complex position within the colonial state.

First of all, the chopping-off-hands stereotype needs to be nuanced. An analysis of the few preserved theft cases, tried at regional law courts (landraden) in Java from 1820 until 1842, shows that out of 25 theft cases the penghulu recommended “potong tangan” six times.

Second, the early nineteenth-century case files do not substantiate the alleged passive attitude of the penghulu either. On 16 January 1826, for example, the penghulu at the landraad of Tangerang recommended a relatively mild punishment of “no more than thirty rattan strokes” for the farmer Oetan Bappa Leha, who had stolen food to feed his hungry family. The prosecutor, however, pleaded for three years of chain labour. Oetan Bappa Leha was sentenced to a punishment milder than the prosecutor’s plea, although the verdict was still harsh: chain labour for one year preceded by thirty rattan strokes, to be executed at the bazar. He also had to return the stolen rice.

Court case files like this, where the penghulu actively advised against the prosecutor’s plea, show a more active role of the penghulu in legal proceedings than the stereotypical descriptions in colonial Dutch lawyers’ writings.

And the files show something else. Most strikingly, also in cases where the penghulu’s advice did not involve any mutilating punishments, the landraad would often still ignore his advice altogether and instead apply one of the colonial regulations.

The negative stance of Dutch colonizers vis-à-vis Islamic law in Java intensified during the nineteenth century. Ironically, also among the Javanese population, the penghulus were increasingly portrayed in a negative light. They were regularly accused of collaborating with the Dutch. As historian Muhamad Hisyam has argued, the penghulus found themselves more and more situated “between three fires”: God, the Islamic communities in Java, and colonial rule.

Despite the damage done to their reputation, the penghulus continued to be active as presidents of the semi-independent religious courts, and also continued to provide legal advice to Dutch and Javanese judges of colonial law courts until 1942. After decolonisation they disappeared from the pengadilan negeri, the postcolonial regional law courts. Penghulus nowadays are marriage officials.

The rationale behind the consultative role of the penghulu in the colonial courtroom had been that the Dutch judge was not knowledgeable of local and Islamic laws and therefore needed a local intermediary to implement the stated goal of applying local laws for the local population. In reality, however, instead of taking the advice of the penghulu into account the Dutch judges started to ignore it altogether. They reduced the complexities of implementing Islamic and customary law in a colonial court to a rather simplistic image of the application of Islamic corporal punishments. In this way, the Dutch colonizers pretended to apply Islamic and customary law through the presence of the penghulu in the courtroom, while in reality they imposed unequal and uncertain colonial regulations on the local population of Java.

Sanne Ravensbergen is interested in collecting more information about the role of the penghulu in colonial and religious law courts. If you have (or know of) stories, memories, archival documents, photos or other information that you would like to share with her: s.ravensbergen@hum.leidenuniv.nl

0 Comments