Between Family, Islam, and State: Marital Dispute and Divorce in Senegal

In Muslim contexts across the world, sharia family norms tend to operate among a variety of other normative orders. How do sharia norms function in the secular Muslim majority country of Senegal? Annelien Bouland shares some of the findings of her PhD dissertation.

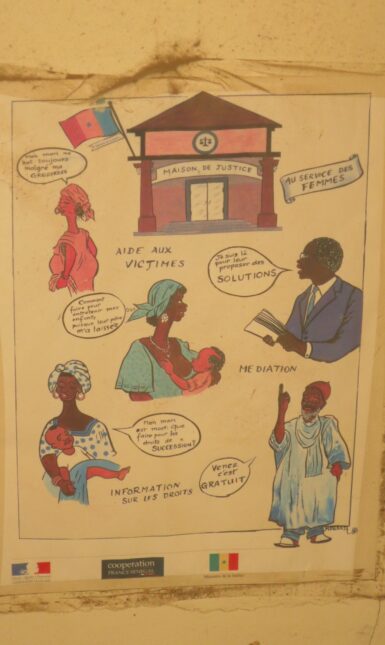

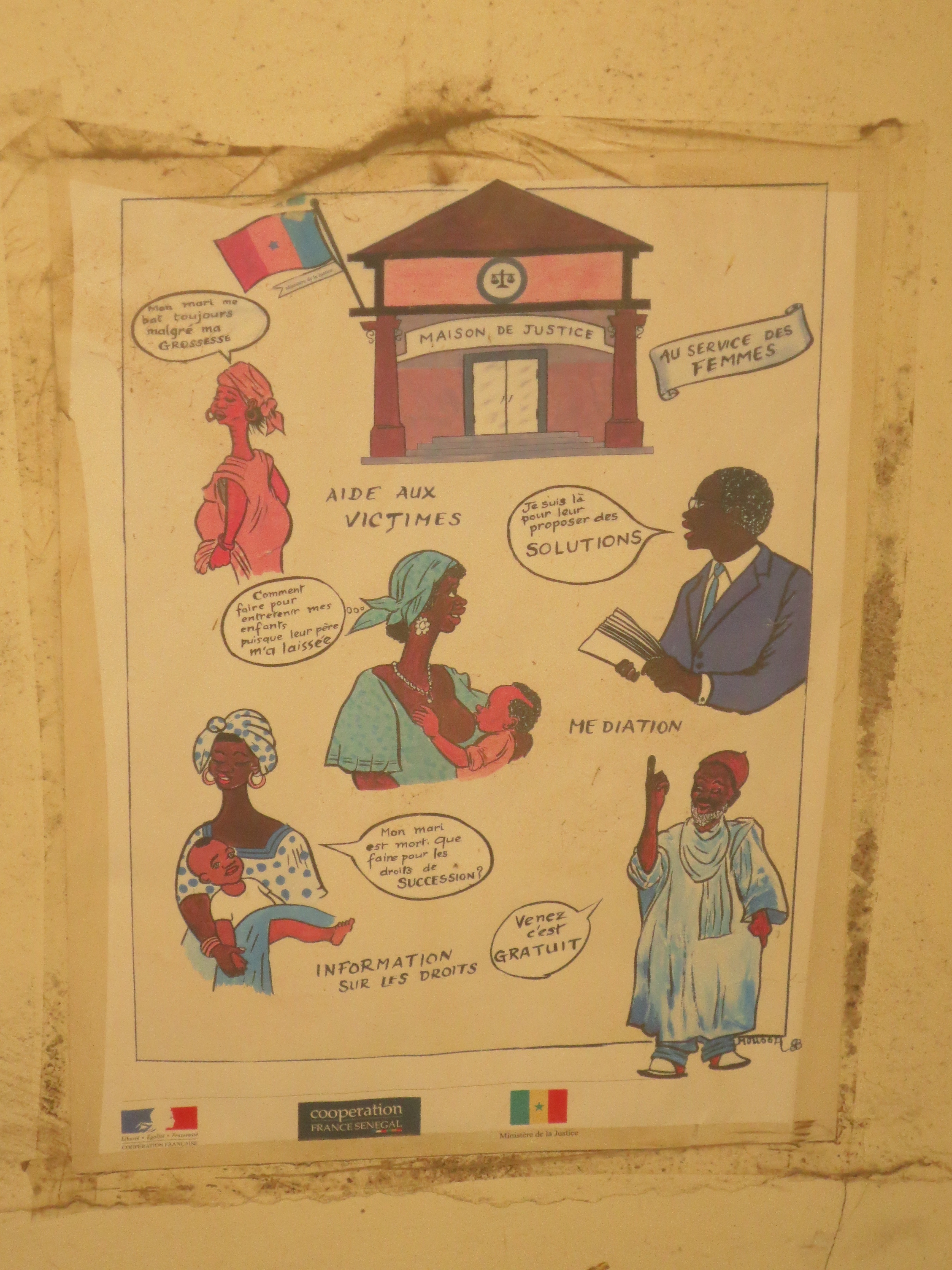

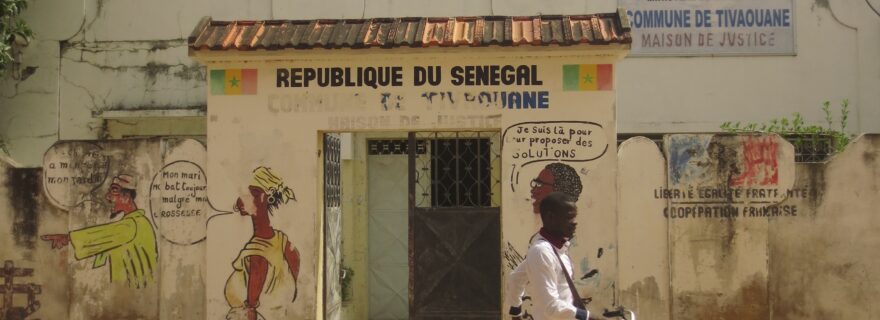

‘Why Muslim women?’, the coordinator of the House of Justice asks. I am visiting the House of Justice to present its staff with some of the findings of my PhD research. The PhD is the result of fieldwork in the Senegalese secondary city of Tivaouane (2016–2017), which I conducted partly at the state institution of the House of Justice. My title, ‘“Please Give Me My Divorce”: An Ethnography of Muslim Women and the Law in Senegal’, seems to make the coordinator feel uneasy. ‘Why not Senegalese women?’, she continues. She adds that Senegal is a secular state and that women like her navigate between, on the one hand, the law and, on the other, Islam. Of course, I had hoped the coordinator would be a bit more enthusiastic about the title. Yet her remarks point precisely to some of the tensions I examined in the dissertation. An interesting discussion about my findings between the coordinator, myself, and the rest of the staff unfolds.

Senegal, a country with an overwhelmingly Muslim (94%) – generally Sufi – population, is formally secular. Still, the country’s Family Code is influenced by both French civil and Islamic law. The 1972 code brought an end to the plural legal system created by the French colonizer in which the native courts that applied – often so-called ‘Islamized’ – custom existed next to a number of civil law courts and Muslim tribunals. During its drafting, custom and Islam were used in almost interchangeable fashion, and the code includes explicit references both to Islamic law and to custom. When it comes to marriage, the code recognizes a civil and a customary variant, where the latter is performed in accordance with (a recognized) custom and subsequently recorded. In practice this often amounts to the conclusion of an Islamic marriage contract. Polygyny is allowed up to a maximum of four wives (art. 133) and the husband is the head of the household. The code prohibits repudiation and other forms of out-of-court divorce. Divorce takes place in court and is the result of either the spouses’ mutual consent or a contentious divorce procedure. Grounds on which the judge may pronounce contentious divorce include, for instance, neglect of the wife by the husband, desertion of the family home, and adultery. The tenth and final ground of ‘mutual incompatibility rendering continued marriage intolerable’ makes divorce an option for anyone who wants to end their union. For Senegalese judges, a spouse’s wish to divorce means that ‘continued marriage’ becomes ‘intolerable’.

Yet almost fifty years after its creation, the influence of the Family Code on the way Senegalese people marry and divorce is limited, to say the least. During my research among Muslims in Tivaouane it became clear that Muslims often failed to record their marriage. Divorce moreover overwhelmingly takes place out of court. If divorce is at the initiative of the husband, he repudiates his wife, where the single utterance of ‘I divorce you’ (fas na la, Wolof), tends to suffice. If divorce is at the initiative of the wife, she asks for divorce (may ma sama baat, Wolof). The husband may accord or deny this request. If he denies the request, the woman will try to mobilize male kin to convince him. People prefer to avoid the court for two main reasons. First, the Family Code is criticized for contradicting Islamic rules on marriage, family, and divorce. Important points of contention are the prohibition of repudiation, the facility for women to obtain divorce, as well as the post-divorce rights a woman may claim. Second, there is a strong preference for informal, amicable and ‘private’ solutions. To bring a divorce to court is to air one’s dirty laundry in public.

It is clear that Maliki interpretations of sharia family norms play an important role in ‘customary’ marriages, out-of-court divorces, and the handling of marital disputes in Senegal. They are often justified in terms of their Islamic character. By contrast, in court and at the House of Justice people are not formally met as Muslims. Still, a number of norms in the Family Code derive from Maliki interpretations of sharia. All the same, people are critical of the code and rather tend to proceed outside these state institutions. They prefer not to register their customary marriage and not to bring their family problems and divorce cases to the court. This tension between state and Islam is precisely what the coordinator was referring to. Women in particular may need to make difficult choices between the informal spaces of Islamic norms and the House of Justice and court, where they may secure a number of rights that are hard to obtain without calling on the state.

On 18 May 2022, Annelien Bouland publicly defended her PhD dissertation: ‘“Please Give Me My Divorce”: An Ethnography of Muslim Women and the Law in Senegal’. Between 20 April and 4 May 2022 she was in Senegal to share the results of her research.

0 Comments